Forgotten transnational solidarity between the Americas

Today I enthusiastically welcome scholar Erina Duganne who, in keeping with previous posts on archiving activist art, looks-back to 1984 at Artists Call Against U.S. Intervention in Central America

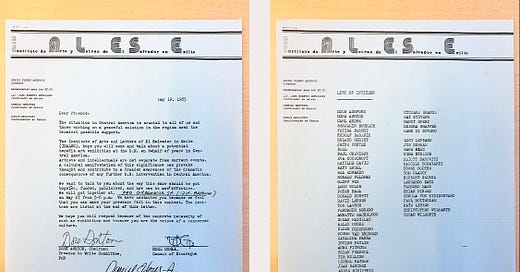

On May 27, 1983, as the Reagan administration amplified their interventionist policies and U.S. sponsored violence in Central America, a group of artists, activists, and writers from across New York City gathered at artist (and member of PAD/D) Herb Perr’s loft on Greenwich Street. The impetus for the gathering was a letter, sent several weeks earlier, on behalf of the newly formed Institute of Arts and Letters of El Salvador in Exile, or INALSE. In this letter, Dore Ashton, Noel Corea, and Daniel Flores y Ascencio invited recipients to discuss the possibility of organizing a joint exhibition and action at the UN in support of “peace in Central America” and to amplify “broader awareness of the dramatic consequences of any further U.S. intervention in Central America.” This proposition received enthusiastic support. In fact, there was so much buy-in from attendees, including those who had never previously given Central America much thought, that a more ambitious program was proposed. This platform, and its twenty-five-member ad-hoc committee, which included, among others, Doug Ashford, Julie Ault, Fatima Bercht, Josely Carvalho, Daniel Flores, Leon Golub, Kimiko Hahn, Jon Hendricks, Tom Lawson, Lucy Lippard, Juan Sánchez, and Coosje van Bruggen, became the basis of Artists Call Against U.S. Intervention in Central America.

Artists Call was formed in the shadow of the Central American peace movement. But whereas this more well-known effort, made up largely of grassroots, campus, church, community, and non-profit organizations, tended to use direct actions, civil disobedience, and congressional pressure to protest U.S. intervention in Central America, members of Artists Call employed different tactics. Wanting to imagine a future outside of the political structures of imperialism and neocolonialism, Artists Call instead sought to build what I call “visual solidarity.” Artists Call’s activism, in other words, went beyond instrumental purposes to prefigure the social relations, cultural practices, and political structures, including anti-imperialism, its members wanted to see visualized in the world.

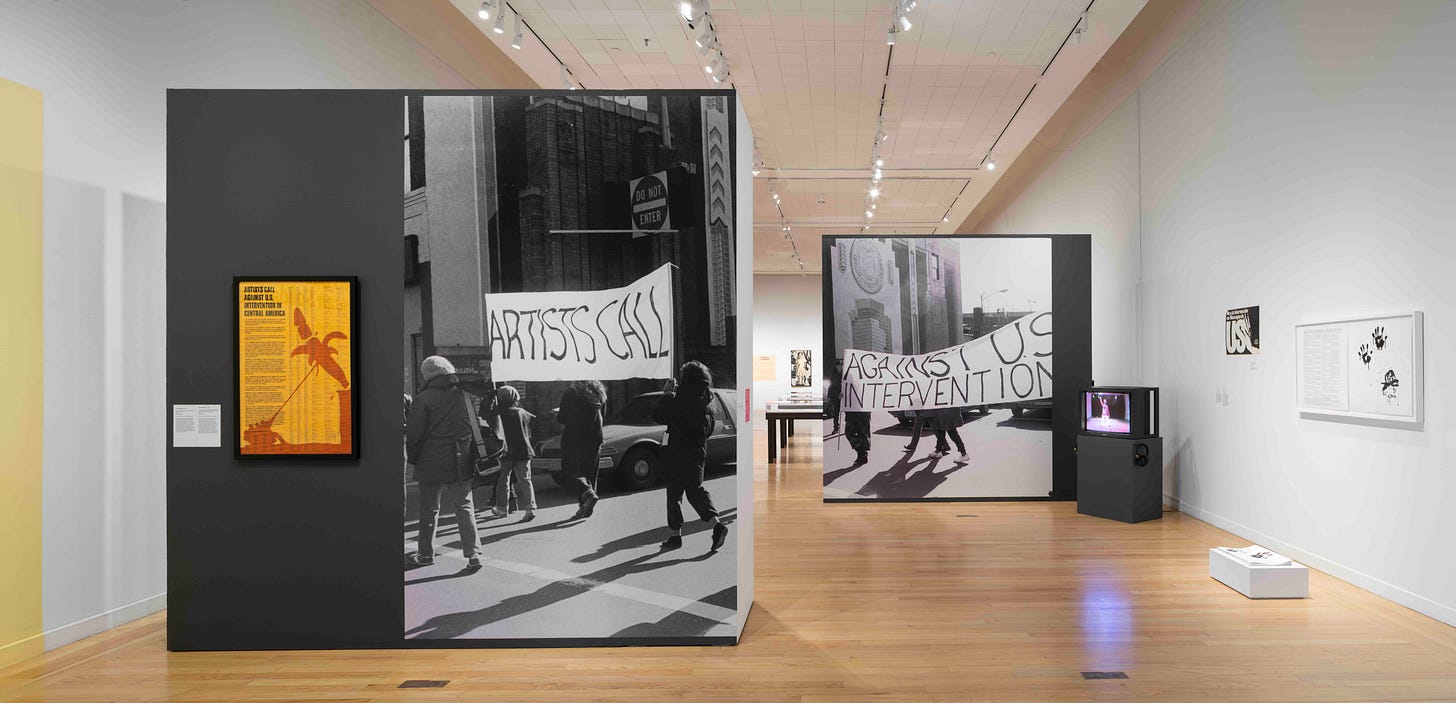

To that end, the campaign showcased not only art works made about Central America but also those made in diverse styles, media, and themes in support of as well as from Central America. These works, in turn, were not just exhibited in alternative art spaces such as ABC No Rio and Fashion Moda. In New York City, where the campaign began in January 1984, a group of over one thousand international artists participated in thirty-one exhibitions that took place at venues ranging from Judson Memorial Church to the New Museum of Contemporary Art and at such commercial galleries as Leo Castelli and Metro Pictures. There was also an eight-night performance art festival, music concerts, film screenings, poetry readings, demonstrations, street actions, and more. Just as importantly, Artists Call’s reach extended beyond New York, with events taking place in over twenty-seven cities across the United States and Canada.

But despite this phenomenal success, in May 1984, just four months after it premiered, Artists Call’s New York campaign came to an end. At this meeting, held at the loft of Leon Golub and Nancy Spero, some attendees proposed using the money Artists Call had raised, as Doug Ashford recalls, “to create a longer-term organization…for continuing the work [Artists Call] had completed.” Jon Hendricks, who was also present, however, spoke out against this proposal. As a longtime artist activist and someone who had been a part of the campaign since its beginnings, Hendricks argued that Artists Call’s formation had always been conceived as temporary and so should disband. This position held sway. “In the end,” as Ashford continues, “we voted to stay consistent with our goals stated initially: we sent the money to cultural workers in the region and began our work again in new areas of concern.”

With the dispersal of Artists Call also came inattention. Until my serendipitous discovery of them in the summer of 2015, twelve boxes of archival materials related to Artists Call sat forgotten, apparently since the 1990s, in New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Queens Library, where they were erroneously listed as part of the PAD/D archive. This past year, the materials were unexpectedly transferred to MoMA’s Archives and, most importantly, catalogued. Though MoMA has never said so, I am certain that the 2022 exhibition and illustrated catalogue, Art for the Future: Artists Call and Central American Solidarities, that I co-organized with Abigail Satinsky for the Tufts University Art Galleries, and which subsequently travelled to the University of New Mexico Art Museum and the DePaul Art Museum, played some role in this relocation. When I unearthed these archives in Queens nearly a decade ago, I made a promise to Doug Ashford that they would become the basis of an exhibition project as well as a scholarly monograph. I am hard at work on that second project now.

Erina Duganne is Professor of Art History at Texas State University, where she teaches courses ranging from the history of photography to Latinx art history. Her research and writing address three interrelated areas: artist activism and solidarity practices; documentary photography and its histories; and race and its representation. Her current book project, supported by The Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant, looks at the solidarity practices of the short-lived 1984 activist campaign, Artists Call Against U.S. Intervention in Central America.

RELATED: PAD/D, Political Art Documentation/Distribution Archive at the MoMA