FIELD Journal Global Updates: Part One

Reports on International Resistance to Neoreactionary Nationalism: 2025

Many people will remember 2016 as the year global politics got weird. The UK began a sharp turn against neoliberal globalism via Brexit, and the U.S. elected a predatory, tax-evading, real estate speculator and TV entertainer as President of the United States for the first time. And yet, these events joined with an already existing rightward change already taking shape across the globe. Later the following year, and with Grant Kester’s endorsement and encouragement, I began contacting international colleagues invested in progressive, socially engaged art and protest culture asking them for reports on local conditions. Over thirty responses came in from regions in Northern, Central, Southern and formerly Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Far East, North and South America, Australia and Africa. My proposal to Grant at the time was to consider revisiting this issue in ten years. Little did I suspect how time flies.

Now, in 2025, that decade has essentially just come and gone in less than 7 years following the reelection of that same rogue politician and his sycophantic acolytes who collectively control $340 billion of wealth, compared with about $118 Million belonging to outgoing president Joe Biden and his cabinet. The United States is now unquestionably being governed by an elite oligarchy controlling both concentrated power and capital. But even more alarming is the anti-progressive and ultra-nationalist bent of this circle that also exhibits unmistakable authoritarian tendencies. Again with Grant’s input and support we realised that another, updated set of global reports was needed sooner than later. However, rather than publish these studies all at once as was done for FIELD issues 12/13 in 2019, we have decided to begin with a few and continue adding new entries to these accounts for the journal issues yet to come. The primary question each correspondent has been asked is,

In light of the far-right parliamentary shifts in your nation, what difficulties have arisen or do you see on the horizon to thwart progressive objectives especially as these exist within the sphere of arts and culture, and if relevant, how have these evolved over the past six to ten years?

KEEP READING: https://field-journal.com/issue-29-winter-2025/2025-global-update/

Austria on the Far-right Frontline

by Oliver Ressler

In February 2000, Austria’s conservative ÖVP formed a coalition with the far-right FPÖ[1]. Back then, this was a taboo. Austria was the first European Union state to include a far-right party in its government. The EU imposed diplomatic sanctions on Austria. Inside Austria there were huge demonstrations against the government. There were also many inspiring initiatives within the arts scene: The Diagonale Festival of Austrian Film introduced a dedicated section for film formats opposing the government, Die Kunst der Stunde ist Widerstand (The Art of the Hour is Resistance). The magazine Camera Austria published an entire edition consisting solely of black pages, titled Austria 2000.[2] In Austria’s capital, Vienna, weekly demonstrations took place every Thursday. These Donnerstagsdemonstrationen began outside the Office of the Federal Chancellor and took a different—unannounced—path through the city each week, often venturing to the party headquarters of ÖVP and FPÖ, or disrupting events involving governmental ministers. At first, a few thousand people took part. They continued for months afterwards with crowds of a few hundred. The art initiative Public Netbase was among initiators of Volxtanz, a mobile DJ platform that moved across the city, bringing together DJ mixing, dancing and art activism. This format lasted several months, mobilizing and politicizing a younger generation. After February 2000, most art institutions decided to ban MPs from speaking at openings, refusing to allow art to become a platform of representation for politicians[3].

KEEP READING: https://field-journal.com/issue-29-winter-2025/austria-on-the-far-right-frontline/

From Marginality to Power: The Rise of Far-Right Politics in Portugal and the Potential for a Common Struggle Between Artists and Broader Society

by Cristina Pratas Cruzeiro and Raquel Ermida

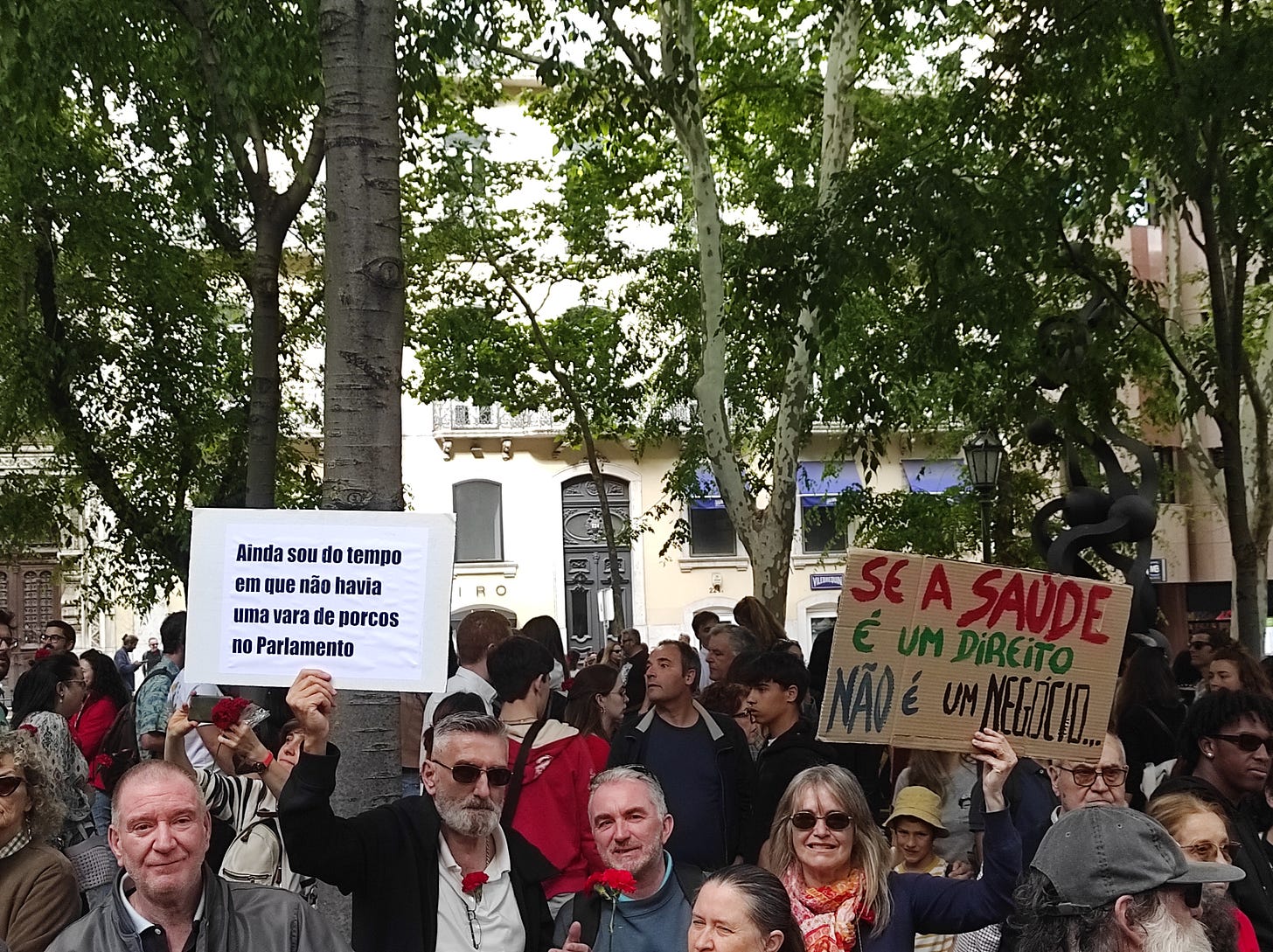

Fifty years ago, in 1974, Portugal overthrew a fascist-leaning dictatorship through the April 25 Revolution, founded on democratic and progressive principles. Since that time, far-right movements and political organizations have existed in the country. However, the Revolution fostered a broad social consensus around democratic values, rooted in a rejection of authoritarianism, which kept these groups relegated to social and political marginality until 2019 (Fig. 1). 2019 marked a turning point when, for the first time, a deputy from a conservative, populist, and xenophobic party was elected to the Portuguese Parliament. This election signaled the institutionalization of far-right ideology in Portugal, aligning the country with a trend that had been gaining momentum across much of Europe for years.

By 2024, the far-right party achieved a startling breakthrough, electing 50 deputies and becoming the third-largest political force in Parliament. This electoral success has significantly reconfigured parliamentary dynamics, pushing right-wing parties toward more extreme positions, for example, on abortion laws (legalized in Portugal in 2007), immigration controls, and social welfare[1]. While such policy objectives have periodically resurfaced when the so-called moderated right-wing parties held power, they were historically unsuccessful due to insufficient parliamentary representation. The strengthening of the far-right has now tipped the balance, increasing the likelihood of alliances and policy regressions.

KEEP READING: https://field-journal.com/issue-29-winter-2025/from-marginality-to-power/

Laboratory Italy: The Meloni Government and Postfascist Intellectuals

by Marco Baravalle

The newly elected (2022) Meloni government in Italy is pursuing three major constitutional reforms. First, they propose changing how the prime minister is selected – moving from the current parliamentary appointment system to direct election by voters. This would significantly increase the prime minister’s power by giving them a direct mandate from the people rather than depending on parliamentary support. The second reform concerns regional autonomy. Currently, Italy’s regions have varying levels of self-governance, with the national government in Rome controlling most financial resources. The proposed “differentiated autonomy” would redirect more funding to Italy’s northern regions, which are already the country’s wealthiest areas. This reform appears designed to satisfy Meloni’s coalition partners, the Lega Nord (Northern League) party, which has traditionally represented northern Italian interests and maintains its strongest support in these prosperous industrial regions. The third initiative involves reforming Italy’s justice system, though the specific details of this proposal are not covered here.

KEEP READING: https://field-journal.com/issue-29-winter-2025/8591/