2017: A Week in Havana teaching at Tania Bruguera’s Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt

December 2017.: Parts 1 & 2

A group of wonderfully engaged and enthusiastic artists greeted us in Cuba last week (Dec 19 - 26, 2017) as Olga Kopenkina and I made presentations about our work at Tania Bruguera’s newly established Hannah Arendt Institute for Activism. I began with background lectures on my own, NYC-based cultural activism including PAD/D (1980-1988), REPOhistory (1989-2000), and Gulf Labor (2010-ongoing), as well as such concepts as Dark Matter and interventionist art, while Olga discussed contemporary artists from Russia and Belarus and the post-Communist cultural situation (see below).

Day one went smoothly with about ten students present at the INSTAR space and an initial discussion that pivoted primarily on the differences (or lack thereof) between art and political activism. Its notable that in the US and Europe this distinction remains a largely academic matter, while in Cuba there are real consequences for being perceived as on either one side or the other of this divide as we soon discovered in an immediate and direct way.

Day two’s presentation started with a missing projector cable that actually made the event more intense because those present were forced to crowd around the laptop screen to see images. Noise from the street right outside the door of the presentation room was at times defining so this huddle also helped the translator do his job. After the talking and debating ended for the night several people wanted to attend a theatrical presentation scheduled to take place in a private home in the Vedado section of Havana. Sadly, when we arrived undercover state security men stood outside the house preventing attendance. When several members of our group first challenged this blockade verbally and then attempts at crossing the line the situation soon escalated. Ultimately four people, including Tania Bruguera were taken away by police cars that showed up a bit later. It truly seemed excessive given the event was an avant-garde performance, not a dissident meeting. In the midst of the melee the theater director improvised a dramatic street performance.

Day two’s presentation started with a missing projector cable that actually made the event more intense because those present were forced to crowd around the laptop screen to see images. Noise from the street right outside the door of the presentation room was at times defining so this huddle also helped the translator do his job. After the talking and debating ended for the night several people wanted to attend a theatrical presentation scheduled to take place in a private home in the Vedado section of Havana. Sadly, when we arrived undercover state security men stood outside the house preventing attendance. When several members of our group first challenged this blockade verbally and then attempts at crossing the line the situation soon escalated. Ultimately four people, including Tania Bruguera were taken away by police cars that showed up a bit later. It truly seemed excessive given the event was an avant-garde performance, not a dissident meeting. In the midst of the melee the theater director improvised a dramatic street performance.

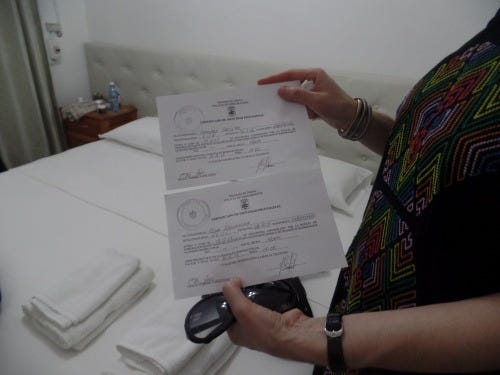

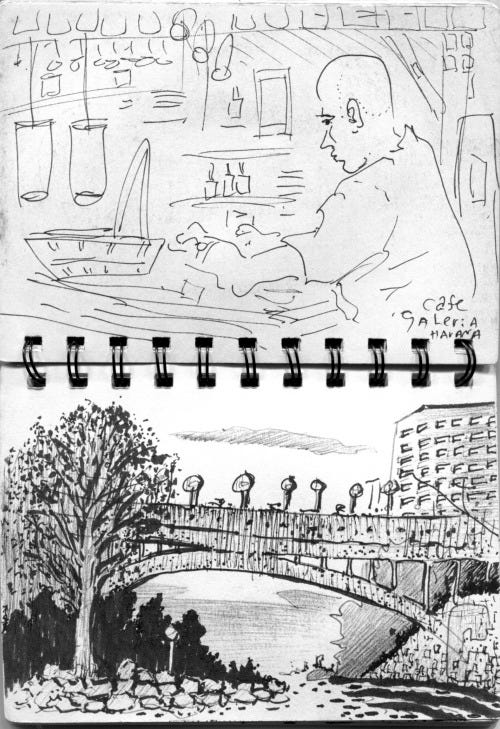

The next morning after returning to our room ( a modest Casa Particular INSTAR arranged for us) from breakfast at our favorite spot, (Gusto Ristorante a few blocks away) the landlady handed us formal papers left by authorities requesting our presence at their offices later that afternoon. Tania also received one. When the time came we found a taxi driver willing to take us to the Immigration Station some distance away and wait for us to take us back again. We sat outside for about half and hour before being escorted inside. I killed time by sketching our waiting taxi and workers at a nearby construction site.

Three men, one in uniform, took our phones (yes, even my antiquated flip-phone) and placed us in a small white room with what appeared to be a mirrored wall to our backs that was covered in floor-to ceiling blinds. One man translated as the uniformed military officer firmly explained in Spanish that we were not to attend INSTAR or any unofficial events and should not spend time with Tania or her students. After all we are not in Cuba to teach because, as they pointed out correctly, we are traveling on tourist visas. Furthermore, they informed us that INSTAR is not licensed as an educational space and that Tania Bruguera is not considered an artist in her home country, but is instead viewed as a political figure. We pointed out that her art hangs inside the city’s National Museum of Fine Arts and she is well-known as an artist around the world. They acknowledged this yet the obvious contradiction did not seem to register beyond a shake of the head. They concluded their hour-long visit/lecture by warning us that we would be punished and deported if we returned to INSTAR (which is also Tania’s home).

We took the next day off not wanting to provoke things further. The day after that we decided to meet with students informally in an outdoor location on the Paseo del Prada, a tree-lined boulevard that sits between Centro and old Havana. A gaggle of song birds roosting in a nearby tree played a cacophonous soundtrack as late afternoon turned to dusk and then into nighttime. Several cell-phones illuminated Olga’s presentation in the darkness. By now the birds were asleep. This was undoubtedly the most robust discussion of the entire trip as the young Cuban artists were keen to know how their no-longer-socialist peers were treated in Russia and Belarus. Olga discussed the works of Petr Pavlensky, Pussy Riot, and Viona,

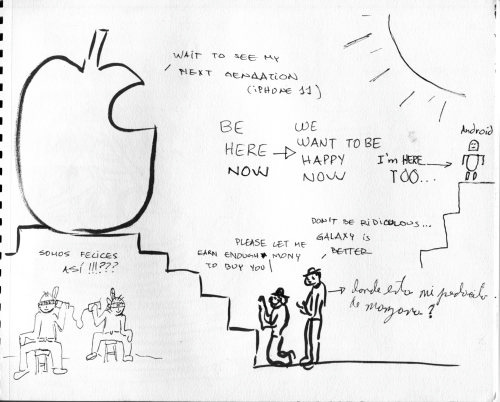

Our final INSTAR event took place in a home-art gallery and included a workshop were participants were encouraged to interact with four cartoon sketches as well as asked to answer “What would you say to Cuba ten years from today?”

Collectively created drawings by INSTAR participants and us:

As we waited for our return flight to NYC three men approached us asking for our passports. Once they identified us we were escorted from the general boarding area and into another small white room located in a nondescript corridor of José Martí International Airport. One man was the military official from several days before, only now dressed without his medals, military uniform and so forth, and I noticed he had his ID tag turned around to obscure his name. Much of the lecture this time was the same, though with more intensity and greater insistence that Tania is not an artist and she should not be associated with by us or any artists from outside Cuba. I commented that I am for the revolution but it really needs a bigger heart and should embrace its critics, a gesture that would in fact make Cuba stronger in the eyes of many. Olga added that her own parents -Lilya and Ivan- were Soviet engineers who helped build the infrastructure of revolutionary Cuba. The authorities assured us with a bit of glee that they already knew all about us.

After returning to NYC were discovered that Tania was again detained and interrogated and that the state is now seeking to confiscate her home (the location of INSTAR). The steady pressure is quite cruel and unnecessary for someone who to my mind has the ideals of the revolution as her goal. To cite Fidel Castro from one of his last speeches “The equal right of all citizens to health, education, work, food, security, culture, science, and wellbeing, that is, the same rights we proclaimed when we began our struggle,” Still, in a radical socialist society equal right to culture should not mean access only to art that is certified by the state. After all, as Marx commented 170 years earlier in one of his rare proposals for the future:

Though that ideal communist subject is ever harder to imagine as we are increasingly surrounded and permeated by a desperate and voracious form of what Peter Fleming calls the “smash-and-grab era of capitalism,” the cultural arena remains one space where such prefiguration should not only be possible, but demanded, especially in a revolutionary society pre or post Fidel.

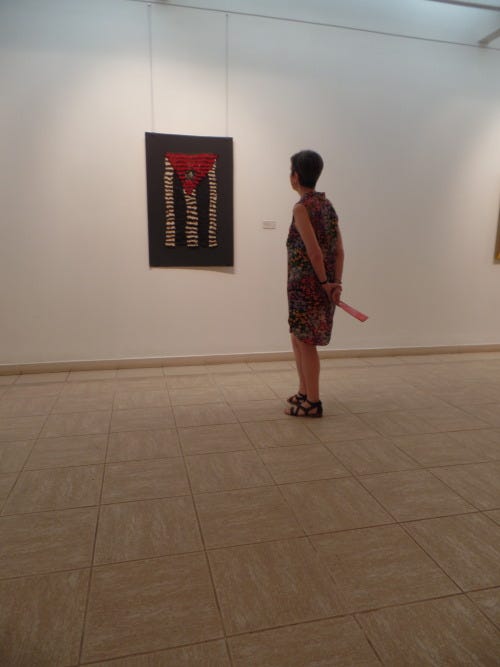

Artist Tania Bruguera’s work hanging in the National Museum of Fine Arts

Part 2: A Week in Havana at INSTAR

Lets discuss our experiences here in Havana this past week Olga.

Isn’t that a bit narcissistic?

We have ordered breakfast out-of-doors at our usual spot –“Gusto’s” at Calle N,– but as our dollars vanish with no hope of replenishment here in Cuba our meals are becoming increasingly frugal.* This morning it is one Cuban pancake and one Americano or Café con leche for each of us. The predicament leads to increased attention regarding what is on our plates. Here we sat, two relatively privileged Americans subjected to a lesson in economizing that most Cubans experience 24/7.

No. Not self-indulgent. I really think people will be interested. The fact that you grew up in a sister socialist country of Belarus during the Soviet era, I think that has made people here ask “what do you think of Cuba today?”

BTW your hotcake is different from yesterday. It’s different in color, structure and maybe it is ideologically not the same as yesterday.

I look down at the single, crepe-like cake laced-over with dribbled honey. I note that the honey is definitely the same as before, with the same strong floral fragrance that offers relief from Havana’s automobile fume-filled atmosphere.

Maybe they re-engineer their cakes everyday, testing new possibilities with each batch?

Sure. Cubans do seem particularly clever at reimagining and reusing what limited materials they have to work with. We then agree that this tendency is really the underlying national aesthetic: the principal of creative re-engineering and reuse. A revelation made possible by a couple of hotcakes no less.

While I was growing up in 1980s USSR we always had a fairly accessible black market, Olga points out. Those things we could not obtain above ground were available, though for a price of course. But here in Cuba not only do people have limited surplus cash, but they have learned to invent an approximation of the things they want whatever is at hand.

You mean like that building we saw in the poor area of Vedado on which someone had pasted linoleum floor tiles on the front to give it a more eloquent appearance? That is what I am talking about.

“Dragone” a revolutionary makeshift tank/tractor: Museo de la Revolución

Although I have to say Olga that this reminds me of your Russian friend, the artist Vladimir Arkhipov who collects makeshift objects in a sort of ethnography of ad-hocism.

Yes, there is Russian creative re-engineering as in all precarious societies, but it did not then, and does not now, define the national aesthetic (if one exists), not in the way it seems to do here in Cuba.

Our attention shifts across the street to the towering FOCSA Building. At thirty-nine stories it is the tallest in Havana. Built the year I was born (1956) and three years after the revolution began, but also, three years before the rebels finally ousted Batista’s corrupt regime in 1959, FOCSA is considered a marvel of civil engineering. And it is indeed impressive. Now, looking up in the morning light the FOCSA’s curved concrete exterior catches the sun and sends warming air upwards where a dozen or more large black Turkey Vultures circle, taking advantage of the building’s singular thermocline.

What is really puzzling from where we sit is just how and where one enters the building because it looks as if all the impressive stack of upper floors sit atop a completely different structure not visibly connected to what towers above it. But on crossing the street we discover a large, dark tunnel running beneath FOCSA lined with mostly empty retail shops, some black-market money changers (who we ignore), and ultimately a central, open-air atrium where tropical plants have gradually taken root.

Our Rough Guid informs us that somewhere inside FOCSA there is the legendary La Torre restaurant overlooking the Malecón and the Gulf of Mexico. Unfortunately, we are too broke to even grab a beer there at this point. Looking up the buzzards have dissipated, fanning out over the rest of the city for a meal from their elevated roosts on top of FOSCA. Bringing us back to our impressions of the Cuban character.

I think Cubans have a depth to them that I don’t recall in other expressions of national character, Olga comments. It’s a kind of sorrowfulness, but also a visible respect for other people’s inner selves and a regard for the pleasures and tears of other citizens.

I know what she means, though it seems like an odd outcome for a socialist country.

II

A tip from American artist Terrance Gower sends us to off to visit the Russian Embassy in Havana, which is rumored to be an extraordinary example of institutionalized post-war modernism. By chance the driver we encounter near our place of stay leads us to a vintage Soviet era Chaika limousine. It’s not too long of a drive down around the Malecón to the Miramar district where the building sits nearby other national embassies. Our driver waits for us as we jump out for a closer inspection. Designed in 1985 by Aleksandr Rochegov who was later awarded People’s Architect of the USSR in 1991 (this according to Wikipedia though curiously the USSR dissolved a year earlier in 1990, go figure).

After we arrive Olga speaks first: It looks like a brutalist-constructivist hybrid, no?

After a couple of camera clicks each the Russian embassy guards notice us and insist on no more photography. We oblige. But directly across the street sits the far humbler embassy building of Belarus, and I did take a picture of Olga standing before it to show her parents.

IV

The door reads OPEN STUDIO where INSTAR participants wait for us on Monday, December 25th. Early Led Zeppelin plays in the background from unseen speakers. By now the discussion that ensues immediately turns to the Cuban artists favorite conversation: how Cuba is perceived by outsiders. This includes a focus on the recent death of Cuba’s revolutionary leader Fidel Castro last year.

My opening provocation asks, when father is gone the niños y niñas express their true feelings about him, no? But I wonder who becomes the new parent once the mutiny ends?

NO MORE PAPAS! [The artists present chorus.]

Yes, of course, we should all be orphans, but in the US of the 1960s’ young people massively rejected the culture of their parents. Except some ten years after and with no one to rebel against there came a consumer-oriented “me” society that has made all of us highly isolated despite the emergence of cell phones, social media and the Internet.

In Russia, Olga adds, we also lost the papas in the early 1990s, but eventually Putin and the oligarchs stepped in as replacements.

Hmmmm…so is capital becoming the new papa after Fidel? This is when I ask what would you say to Cuba ten years hence? [See previous blog post for some of the responses.]

Still, I continue, what seems most missing today amongst artists is not just the absence of fathers (or mothers) post 1960s, but the long-standing claim of futurity itself. This previous but now missing association is, or was, I assert in full professorial mode now, the invisible link between avant-garde politics and avant-garde art.

One of the artists comments that the early avant-garde did not always focus on the future, for example the Dadaists were more intent on destroying the past, no?

This is when I complete my transformation from mere tourist to “visiting INSTAR professor”:

Yes, the Dadaists were anti-establishment, and yet they also sought to clear space for something totally new to emerge (and perhaps that was Surrealism’s faith in the liberated unconscious life?). We know too that the Italian Futurists called for flooding museums, all the while claiming to envision the emergence of a technologically-focused new society. And needless to say, the Russian avant-garde –the constructivists, productivists, engineerists and so forth– embarked on a collaboration with the Soviet state in order to design a new world for a “new man.” But the art world those of us on the cultural Left have had to live with for decades is far darker. While we may be more realistic than our counterparts from a century ago, that dark futureless is grinding us down fast.

Olga adds that the Left no longer generate charismatic leaders such as Che or Fidel or Lenin. What emerges instead is the technocrat: persons who are more or less good at operating social machinery, though without personality or vision.

Agreed, Greg tacks on, except we find that the Right has stepped into that breach. Whatever else the new US president may be, he is unquestionably one thing, an oversized, populist personality. He may also be the greatest performance artist to date. Its hard to imagine avant-garde artists competing with this man.

Silence.

Somehow we really need to re-invent the concept of the public intellectual. And it is this thought that for has emerged as the most important lesson of the entire trip: how might the Cuban’s aesthetic of reuse be applied to us in the capitalist North in order to regenerate a vibrant, progressive, but also accessible public intelligentsia?

Yes, great, thanks professor, although maybe this is a good time for some more Cuban hotcakes?

IV

Tania’s INSTAR participants are also keen to show us their work on our last day before returning to New York.

Artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara has a passion for first appropriating, and then critically tweaking, popular culture to generate commentary about Cuban art, politics and life. He seems, as many of the artists we met seem, especially focused on the growing Cuban shift from socialist economics towards an embrace of commodity capitalism. This practice of Détournément (though Manuel did not use this term) fits well into the larger aesthetic of reuse witnessed amongst people in Havana in general. For instance the artist transformed a video trailer for Game of Thrones –an illicit yet highly popular television program– into a tightly edited snapshot of Cuba’s political activists and their encounters with police.

We ask him an obvious question: how does he and other Cuban art activists distribute their work given that the Internet is almost inaccessible and that the state has centralized all other media? And let’s not forget situations where undercover authorities show up to physically ban viewing certain art works and performances?

His answer reminds me of 1970s zine culture in the US whereby access to a photocopier at one’s job cheaply reproduced DIY publications making them sharable, or the similar, pre-Internet practice of indi-music swapping using home-produced cassette tapes. Cubans, he explains, combine Blue Tooth file sharing with such content-sharing apps as Zapya. Once again, creative reengineering out of necessity has given birth to a collectively owned work-around solution to both technical barriers, as well as the centralized media system operated by the state.

In another of his pieces we see Manuel holding aloft a four-foot long sledge hammer as if recreating a “workers” stance from some iconic socialist realist painting. Poised before the immaculate glass windows of Havana’s exclusive Giorgio G. VIP retail store, the artist appears about to strike and smash and then presumably be carted off by police, much as witnessed outside the unauthorized performance venue earlier in the week [see part one of my INSTAR blog]. On the other side of the plate glass storefront are racks and bins of fashionable clothing and goods, which, he informs us, sell for 300 times the average salary of a Cuban citizen.

The artist’s tableau vivant seems to ask “Whither socialist equality in today’s Cuba?” And perhaps tellingly, Manuel’s piece is flash-frozen in time, taking the form of a hastily-snapped photograph which he calls “Lo que a Michelangelo Pistoletto no se le ocurrió”, (“What Michelangelo Pistoletto did not think of” in response to the famed Italian artist’s solo exhibition in Havana several years earlier ). The anticipated outcome involving shattered glass, ringing alarms, police respondents and inevitable incarceration remains forever suspended in some time and space that is always elsewhere. Unlike the crystalline VIP store window permitting passersby the allure of luxury commodities, the artist’s alternative elsewhere remains impossible to clearly visualize.

Artist Jose Ernesto Alonso Fernandez also commandeers popular culture and technology in order to dryly remark upon aspects of modern Cuban society. In one project he tracked the current whereabouts of his own high school graduating class from over a decade earlier. Both he and they attended a select education program with an accelerated learning curriculum. Gathering the yearbook photos of his peers into a modernist-like grid, Alonso also color codes their portraits to reveal that some 70% had left Cuba, thus visualizing what he sees to be the brain drain of Cuba’s future.

Another piece directly challenged the briefly warming (though now cooling) embrace of Cuba initiated by the United States under President Obama. Alonso reproduces a scandalous 1949 photograph of a US Marine urinating on the statue of famed national leader and poet José Martí in Havana’s Parque Central. At the time, the image went “viral” long before that concept existed, ultimately helping spur resistance to colonization on the part of affronted Cubans. Alonso reproduced the image some 65 years later as a street flyer in 2014 as his cautionary response to Obama’s visit –the first ever to revolutionary Cuba by a US president– with the words “Perdono Pero Nunca Olvido” (“I forgive but I never forget”) across the bottom of the page, and then proceeded to paste these leaflets illegally in the streets. He then tried to record the public response by documenting the speed that these flyers were torn down by residents or authorities or whomever.

Several other artists also shared their projects with us inside the modest, street-level studio come-art-gallery (which Cuban authorities informed us later is also “illegal” and should not be visited again).

Martha Iris Pérez Santana presented a series of photographic self-portraits in which distorting lenses fracture her body into colored shapes resembling 1950s abstract canvases. Her most recent works take on a darker tone by incorporating implements of bondage and torture, though still remaining within a landscape of abstraction. Her application of low-tech methods (shooting her camera through pieces of faceted glass) reiterates the aesthetic of reuse and reinvention we found reflected in other aspects of Havana’s streets and day-to-day life.

Far more explicit and unsettling are drawings and large photographs by Yuri Obregón Batard’s

http://yuriobregon.com/

combining BDSM imagery with scenes of Havana including the Plaza de la Revolución (the same location Tania Bruguera performed Tatlin’s Whisper #6 in Dec 2014

and where she was arrested and stripped of her passport while attending a political event by activists as she did research for the Hannah Arendt International Institute for Activism that was inaugurated that same month).

Notably, many of the artists we met were not graduates of Cuba’s famed educational system including Instituto Superior de Artes (ISA) which Tania Bruguera attended before graduate school at SAIC (The School of the Art Institute of Chicago were we first met in 1999 when I taught there), though some have degrees in Philology, Engineering and Art History. When this fact is added to the gritty, often socially critical or outright sexualized nature of their practice the outcome tends, as we came to know firsthand, to result in disapproval by the official cultural state apparatus, sometimes to the point where an artist, with Tania as a case in point, becomes persona non grata.

One of the most accomplished artists we encountered was Leandro Feal Bonachea, a graduate of ISA and several other prestigious art training programs in Cuba including Bruguera’s first informal and also unofficial pedagogical experiment Arte de Conducta between 2003-2009. Feal’s bittersweet, black and white photographic diaries of Havana’s robust and sometimes coarse nightlife, his startlingly direct portraits of citizens, and his fascination with the history of photography from the Cuban revolutionary tradition to Nan Goldin’s grainy dark documentation of East Village denizens in the 1980s pinpointed for us the curious mix of nostalgia, ire, sadness and hope that ran through our encounters in Havana like a dusky red thread.

IV

On Tuesday, December 26th we returned to Inwood, or what I call “Upstate Manhattan,” though we live on merely another island now it is a relatively short, three-hour flight to and from Cuba. But in this case distance is measured differently of course. Our first disjunctive reentry experience is the sharp seventy degree plunge in temperature. And lLooking back, setting aside the interrogations and cash problems, there are three things that most stood out for me as I contrasted this past week in Havana to my first trip in 2000.

First is the appearance of product advertisements for cell phones and other luxury goods this time around. These ads are still fairly rare, and most are clustered insid or near the airport. But almost two decades ago these public spaces belonged almost exclusively to images of Che, Fidel and the party.

The second noted change is that people looked better clothed and fed. Back in 2000 Cuba was still reeling from the collapse of the Soviet Union and loss of Russian financial and material support. The US embargo had worn down the population. I recall people walking without shoes and everyone quite thin (though their teeth, unlike my own, were remarkably good, which I attributed to the excellent and egalitarian state of Cuban healthcare).

That sense of more abundance also leads me to my final observation: the presence of trash in the streets and parks. Seventeen plus years ago I was struck by the lack of debris anywhere, quite unlike New York City. I chalked this cleanliness to the unavailability of packaged goods leaving nothing to trow away but the previously mentioned reuse of materials Cubans are so good at. However, this past week I was struck by the frequency of blowing plastic bags, polystyrene containers lodged in bushes, and empty soda cans littered about on steps and sidewalks or left behind at the base of monuments. Perhaps Cuba and Manhattan are becoming more alike than it would seem, though not necessarily in ways that anyone would wish to see.

The day after we returned to NYC I got the awful news that my long-time friend Tim Rollins had died (stay tuned for a future blog on his work), but we learned from Deborah Bruguera who lives in Italy that her sister Tania was again detained and interrogated by authorities just after we left Cuba.

Still, it is a pattern that is not at all new for her and for others in Cuba’s art scene. The artist “misbehaves.” State officials detain and question her. The artist is released, and the cycle soon repeats. I had forgotten until I was pulling together materials for this blog post that I had written about Tania’s untitled installation for the 2000 Bienal de la Habana. This was the piece that was shut down by authorities soon after opening presumably because images of Fidel were played on monitors close to men sitting naked in a very dark, sugar-cane covered corridor of the Cabaña Fortress. So it goes as Kurt Vonnegut wrote in his time shifting novel Slaughterhouse-Fine. (To read an excerpt of my Biennial coverage in the journal Afterimage click here: Affirmation of the Curatorial Class.)

And one other thing I discovered upon returning to this island, Afterimage itself, the cultural magazine in whose pages I first published my critical writings, is being defunded after some 45 years in action and will likely soon shut down.

And so it goes. GS Jan 1 2018

* In 2000 it was still possible to withdraw USD from ATM machines or at a bank, but as of now that is not possible, nor is are American based credit cards usable. Although we brought over five hundred in Euros and Dollars Havana has discovered the tourist economy and that amount of money does not go far. In other words, I am sorry to anyone I promised cigars or rum, we just had enough for the airport taxi left over!

“I AM CUBA” shote from a nearby rooftop looking over at FOCSA building.